Department History

The NMSU Department of Astronomy is now an independent department with a full graduate curriculum, state-of-the-art observing facilities, a dozen faculty, and many distinguished alumni. However, things were not always so! This story recounts how the department came to be from very humble beginnings. It is heavily adapted from faculty emeritus Herbert Beebe’s “A History of the Department of Astronomy: New Mexico State University, 1888-1988.”

The Early Days

Hiram Hadley taught a course in astronomy at the local Presbyterian Church in the spring of 1888, just prior to the formation of Las Cruces College in the fall of that year. Astronomy courses were included among the curricular offerings of New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in the 1890s, beginning an only occasionally interrupted string of astronomy listings continuing to the present. The second teacher of astronomy on campus was Clarence T. Hagerty, who offered courses in the nineties and continued to do so through his more than thirty-year career with the college. He left the University in 1925. John William Branson ended a three–year hiatus in astronomy course offerings in 1928 by becoming the second future University president to take up the task. In 1930 Introduction to Astronomy, Math 55, became a regular offering taught by Branson through the fall of 1948. The year that Branson first taught the course was important for another reason, one that must have given his students quite a boost that spring. On March 13, 1930, Clyde Tombaugh’s discovery of the planet Pluto was announced at Lowell observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona

By 1946 Tombaugh had joined the Optical Ballistics Laboratory at White Sands Missile Range where he was a section chief helping to develop tracking cameras. His work on determining the non–existence of small, natural earth satellites brought him to NMSU in 1955 with an office in the Branson library building, working on the U.S.Army supported project as a Physical Science Laboratory researcher. Tombaugh picked up the broken string of astronomy offerings in the fall 1961 by teaching ASTR 210, Introduction to Astronomy, in the Department of Geography and Geology.

When Tombaugh moved onto campus in 1955, he created the Planetary Group, which in six years grew to five members, large and active enough to move to the Research Center building (now the Astronomy Building). Among the first to join Tombaugh was Bradford Smith who set up an observing facility in his own backyard with results promising enough to obtain further funding for a permanent installation on Tortugas (“A”) Mountain, east of campus. This facility utilized the 12-inch Fecker telescope that had been used as a visual instrument in Quito by Jim Robinson and Scott Murrell as part of Clyde’s satellite search program. When the satellite search project ended, Tombaugh requested and received permission from the Army’s Office of Ordinance Research (OOR) to have the telescope transferred to the University. It produced images of the planets that were superior to most of those being published in the astronomy textbooks of the late 50s and 60s, including images made with the 200-in Palomar telescope. The telescope formed the basis for the observing program that was carried out in the Lower Building on Tortugas Mountain(construction completed in 1963).

When Tombaugh joined the Department of Geography and Geology in 1962, he began a decade of growth and development of the academic aspects of the astronomy program. ASTR 210, Introduction to Astronomy, and ASTR 211, Planetology, where taught during fall and spring semesters respectively by Tombaugh throughout the sixties. Practical Astronomy, ASTR 310, was added in the spring of 1965.

When Tombaugh joined the Department of Geography and Geology in 1962, he began a decade of growth and development of the academic aspects of the astronomy program. ASTR 210, Introduction to Astronomy, and ASTR 211, Planetology, where taught during fall and spring semesters respectively by Tombaugh throughout the sixties. Practical Astronomy, ASTR 310, was added in the spring of 1965.

The addition to the astronomy academic faculty, William L. Reitmeyer in 1965 and James Cuffey in 1966, along with Clyde Tombaugh, began the formation of the new astronomy academic faculty. The 1967-68 catalog listed ten astronomy course offerings and announced the arrival of a new major program at the University.

A Department Takes Shape

Vice President William O’Donnell contacted Tombaugh in 1965 and discussed with him the possibility of an independent academic program in astronomy. At that time, the field of astronomy was beginning to blossom from the exciting discoveries made with modern observational and computational equipment and from the newly successful space program. The launch of Mariner 4 in 1964 and its dramatic photographs of the surface of Mars sent back in 1965 struck close to home. Smith, Tombaugh, and the rest of the Planetary Group were carrying out a NASA funded ground–based patrol of the planets. NMSU administrators, understanding that the time was right to proceed with plans for independent academic standing and additional research facilities, carried out further discussions with Tombaugh, Reitmeyer, and Cuffey.

In the late sixties, the University and NASA provided financial support for construction of two new observatory facilities. A twenty-four inch telescope designed by Smith and Tombaugh for planetary photography was built by Boller and Chivens and installed at Tortugas Mountain. Since its first view of the night sky in January 1967, over one million images of planets have been made. The images, which were regarded by the astronomical community to be then the highest quality collection in the world, have been used steadily and are carefully stored in the Astronomy building on campus.

The other telescope site, earmarked for stellar type observations, would need dark skies. Reitmeyer made a survey of a variety of locations in New Mexico, finally settling on Magdalena Peak, on Blue Mesa in the Las Uvas range northwest of Las Cruces. Cuffey, The twenty-four-inch telescope designed and specified by the three astronomers was built by Astro Mechanics and installed in 1968. The Blue Mesa Observatory (see below) served students, faculty, and visitors from 1969 through 1991.

lan Harris, Charles Seeger, and Herbert Beebe were added to the faculty in the fall 1968, spring 1969, and fall 1969, respectively, joining the department of Earth Science and Astronomy headed by William King. The astronomy program started out that fall with three graduate students and six faculty members (Tombaugh, Reitmeyer, Seeger, Cuffey, Beebe, and Harris). In 1970, astronomy separated from Earth Sciences, and the newly independent Department of Astronomy established offices in the Research Center Building. Reitmeyer became the first head of the new Department in the summer of 1970.

Blue Mesa Observatory

Soon after the opening of the Blue Mesa Observatory, Larry Reitmeyer wrote an article for Sky and Telescope (January 1973) that reviewed Astronomy in New Mexico. In the article he described the environment of the Blue Mesa Observatory:

Of more recent vintage is NMSU’s stellar astronomy program. The need for a dark-sky observatory for such work led to the construction of the Blue Mesa station at an elevation of 6,623 feet, some 30 miles northwest of Las Cruces. Both faculty and graduate students use the Astro Mechanics 24-inch f/15 Cassegrain reflector to study a wide range of galactic and extragalactic problems…

Visitors to the Blue Mesa Observatory find the desert and mountain scenery along the road truly impressive. Mesquite, yucca, and cactus carpet the desert floor. The lava beds composing the mountains show reds and browns that contrast beautifully with the desert’s greens and grays and the daytime sky’s intense blue.

The view from the observatory is breathtaking. To the south, east, and west stretch vast expanses of desert, broken only by a few small hills, with mountains in Texas and Mexico usually visible along the horizon. At night, the Milky Way fairly blazes against the blackness of the sky, the Pleiades sparkle, and the heavens are peppered with bright and faint stars. Overall lies a deep silence, broken only by the roar of the generators when they are turned on to provide power for the scientific equipment.

For more than two decades, approximately 75 students, faculty, and visitors used the facility on 1,500 nights and enjoyed the dramatic environment so well described by Reitmeyer: driving a tough vehicle over a rough road; starting diesel generators; checking supplies; preparing meals; enduring moths, rattlesnakes, and clean-up parties; unsticking stuck things; repairing broken things; solving problems; etc. —all without the use of cell phones or a GPS system. They also published over a hundred papers using Blue Mesa data and completed many Ph.D. dissertations. They were very durable individuals.

As with many good things, Blue Mesa Observatory did not continue in its original form, but it does have its own history. Development of the Apache Point facilities and the complexity of maintaining dual sites created an environment that made a 1991 FAA offer highly attractive. When the FAA contacted the University about the possibility of using Blue Mesa as a radar site, the time was perfect for upgrading and consolidating the department observatory at Apache Point, and the FAA was able to provide funding for the move. A new facility was constructed, and the Blue Mesa telescope went to Pittsburg Kansas, where it is now part of the Greenbush Astrophysical Observatory. It is in the capable hands of Professor David Kuehn (NMSU PhD, 1990) of Pittsburg State Univ.

Faculty in the 70s and 80s

Although Tombaugh officially retired in 1973, he continued to attend department colloquia and seminars and regularly worked at his office in the Astronomy Building. Smith left NMSU in 1974 to take a position in the Department of Planetary Sciences at the University of Arizona. R. Beebe replaced Smith on the faculty and continued her leadership role with the Planetary Group. Herbert Beebe became Department Head in the fall of 1974. Bernard McNamara joined the department in 1975 as a postdoctoral fellow supported by a National Science Foundation grant held by Sanders. In 1976 Cuffey retired, and McNamara, whose graduate work was done at Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz, joined the faculty.

The faculty in 1976 consisted of Kurt Anderson, (Cal Tech), Reta Beebe (Indiana U.), Bernard McNamara (U. Cal, Santa Cruz), Larry Reitmeyer (U. Arizona), Walt Sanders (Goettingen), and Herb Beebe (Indiana U.). This group remained stable for ten years, until the retirement of Reitmeyer in 1986. A master’s degree option was added to the PhD program in 1978.

During that ten-year period, the faculty of six published more than one hundred papers in leading refereed journals, led seventeen students through to the doctorate and eleven others to master’s degrees, carried out an extensive and successful search for consortium partners for construction of a large telescope, participated in space missions with planning and data reduction and with ground based planetary weather predictions, operated four observatories, attended international meetings and workshops in ten countries, worked on $8,000,000 ($FY2009) of Federal grant supported research, observed at national facilities on twenty occasions, and generally established an astronomy program at the University with national and international credentials.

During that ten-year period, the faculty of six published more than one hundred papers in leading refereed journals, led seventeen students through to the doctorate and eleven others to master’s degrees, carried out an extensive and successful search for consortium partners for construction of a large telescope, participated in space missions with planning and data reduction and with ground based planetary weather predictions, operated four observatories, attended international meetings and workshops in ten countries, worked on $8,000,000 ($FY2009) of Federal grant supported research, observed at national facilities on twenty occasions, and generally established an astronomy program at the University with national and international credentials.

Scott Murrell

Observing programs featuring the giant planets, Venus, Mars, and comets were carried out by Scott Murrell, who became the mainstay of the Tombaugh-Smith telescope operations. He continued as an observer for 30 years. Throughout his more than 50 years at NMSU Scott played many roles other than observer. His meticulous painstaking care of the observatory darkroom was famous among faculty, staff, and students. However, that aspect of image recording took an interesting turn in the latter eighties. “Wet processing” became electronic as charge-coupled device imaging evolved. With the help of graduate students, David Kuehn and Chris Barnett, Scott mastered this new process of acquiring data and applied his systematic approach to evolve an effective observing routine. It was that adaptability that led Scott to become such a strong contributor to the successful start of the department. He interacted positively with the staff, faculty, and students. Rather than being an inflexible, aging codger, he presented a supportive and encouraging attitude to all

Murrell led VIP visitors on tours of the A-mountain facilities and always left a positive impression. He was a strong advocate for our graduate students, invariably lauding their intelligence and character. He was a good teacher, helping many students to become astronomers.

After Scott Murrell passed away on September 25, 2004, the idea of a departmental memorial fund in Scott’s name was proposed as a means of honoring his memory and allowing his legacy of supporting graduate students to live on. The A. Scott Murrell Memorial Endowed Scholarship Fund was established in December 2004 with some initial anonymous donations and a contribution from Scott’s family. Earnings from this endowed scholarship are used in part to make an annual award that recognizes outstanding research or professional development by a graduate student, and related accomplishments that raise the visibility of the NMSU Astronomy Department. With this endowed fund, Scott’s effect on future graduate students can live on forever.

Apache Point Observatory

Recognized throughout the sixties and seventies was the need for a large aperture telescope to give a permanent basis to world-class astronomy at NMSU. Such an endeavor, even with Federal support, would be costly, and searches were continually made for partners. By 1979 several universities had expressed interest in joining NMSU in developing funding for a large telescope. Trips were made to the Solar Observatory at Sunspot in 1980 to discuss with the observatory’s director, Jack Zirker, the feasibility of constructing the telescope on ground adjacent to the solar observatory. The subsequent search for additional consortium members continued, and Sanders contacted University of Washington astronomers who had funds available and needed a partner. During the period 1980-83, additional consortium members were recruited. Bruce Margon, Univ. of Washington, led the early efforts in the organization of the group. He, Bruce Balick, also of Univ. of Wash., Don York of the Univ. of Chicago, Kurt Anderson of NMSU, Jim Fields with NMSU’s Physical Plant, and many others provided continuity through early stages of the observatory construction.

Financial support was, of course, fundamental to the project, and university participants promised initial and continuing investments. In 1981 the Research Affairs Committee of the College of Arts and Sciences voted to support the project with more than $500,000 of state bond issue funds, and Washington State U., Princeton U., and U. of Chicago joined NMSU and U. of Washington.

At NMSU it was the active support of the Dean of Arts and Sciences, Thomas Gale, which gained our share of the Apache Point Observatory. We also were indebted to the University President, Gerald Thomas, and Associate Dean of Arts and Sciences, Dennis Darnall, who successfully participated in formulating the role of NMSU in the project. As Bruce Margon pointed out at the onset, the observatory is not only a step forward for astronomy but also for the prestige of the participating universities and especially their departments of astronomy, providing also an excellent graduate-student recruitment advantage.

By 1984 the Astrophysical Research Consortium (ARC) was officially formed, plans were firmed to construct a 3.5 meter telescope at Sunspot, and a proposal was sent to the National Science Foundation for funding for about half of what had become a ten- million-dollar project. In 1986 NSF approved its largest grant ever for a University project, almost $4,000,000. Construction was already under way then and was almost completed by the end of 1987. The primary mirror for the telescope— the most difficult of all the steps—was installed in 1989, completing one of the largest university controlled telescopes in the world.

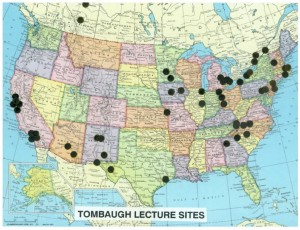

The Clyde Tombaugh Scholar Fund

A fund-raising campaign was initiated in 1986 to establish an endowment for support of post-doctoral fellows, the Clyde Tombaugh Scholar Fund. Bernie McNamara would help coordinate and accompany Clyde on a tour of various cities across the US. A central focus of the fundraising was the amateur community, whose various clubs across the country would plan lecture tours in which large crowds would hear the story of how Pluto was discovered. In addition to an admission charge, an autographed certificate of participation and a poster would be sold.

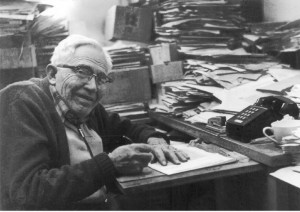

Tombaugh’s health posed a haunting question at the beginning. He had celebrated his eightieth birthday that year. Would he be able to stand what could develop into a grueling series of cross-country journeys and a long schedule of lectures? These fears were nullified after the project’s first few months. In a three-day trip to Riverside Telescope Makers Conference in May 1987, Tombaugh’s spirits surged as he recalled his earlier years to an audience of more than a thousand amateur astronomers. As publicity for the campaign spread, Tombaugh was booked in cities all over the country.

On a northeastern tour in the fall of 1987, Tombaugh’s schedule was intense. In one day he delivered a lecture in Philadelphia and a banquet talk in Bethlehem, appeared on a local radio program, autographed almost one hundred posters, and answered countless questions. The following day he appeared at an executive lunch, and then he

toured an amateur observatory site. That evening he was the guest at a fundraising party for amateur astronomers. In a setting reminiscent of children meeting Santa Claus, the amateur astronomers spent several hours talking with the only living discoverer of a major planet. They saw Tombaugh as one of them, a role he plays well and honestly. A reception the following day was held at the headquarters of the American Association of Variable Star Observers and was also sponsored by Sky and Telescope magazine. Once again Tombaugh signed posters and recounted his discovery.

Bernard McNamara continued his involvement in management and selection of candidates, and the Clyde W. Tombaugh fund has proven to be extremely successful, providing the department faculty and students opportunities to work with extremely bright young astronomers.